By Héctor Alejandro Arzate

After months of uncertainty over its future, an online resource for tracking the financial cost of weather and climate disasters throughout the United States has been revived.

The U.S. Billion Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters database was previously managed by a team at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA. Since 1980, the program has been responsible for analyzing wildfires, tornados, winter storms, and other disasters that cause at least $1 billion in damage. But it was retired in May, one among several NOAA products and services to get shuttered by President Donald Trump’s administration this year.

Now, a non-profit called Climate Central, which communicates climate change science and solutions, has hired the scientist who led the project at NOAA, Adam Smith, and has taken on the responsibility of compiling and releasing the latest data.

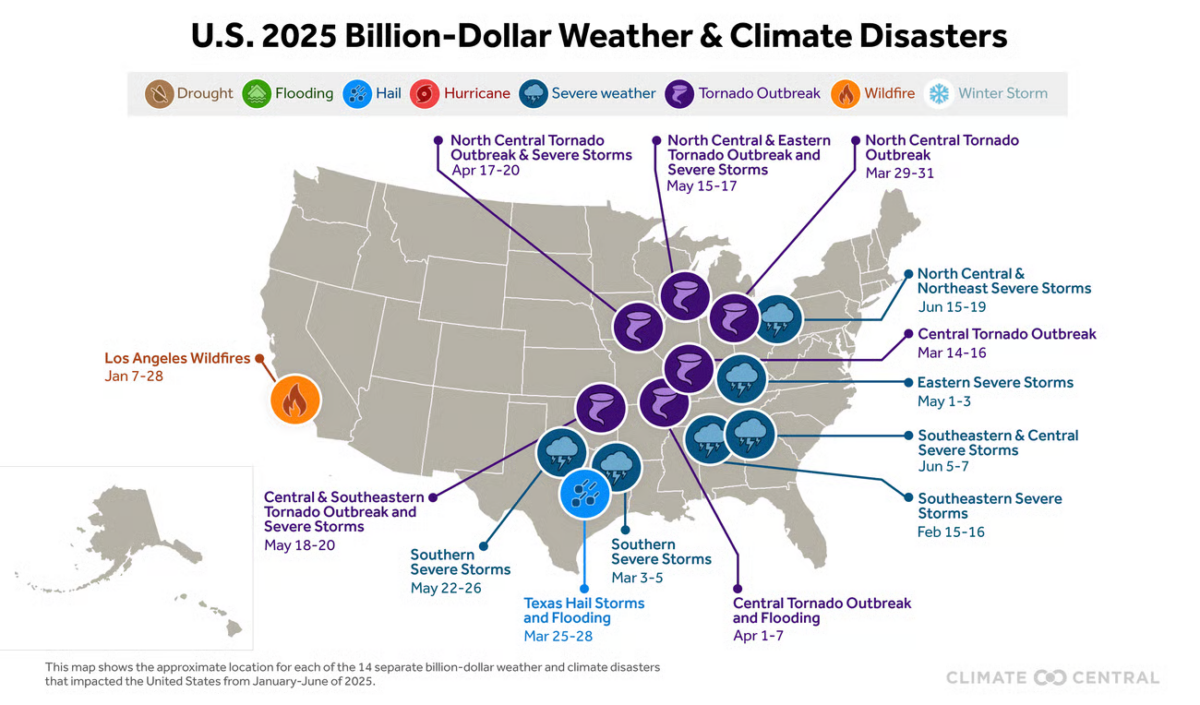

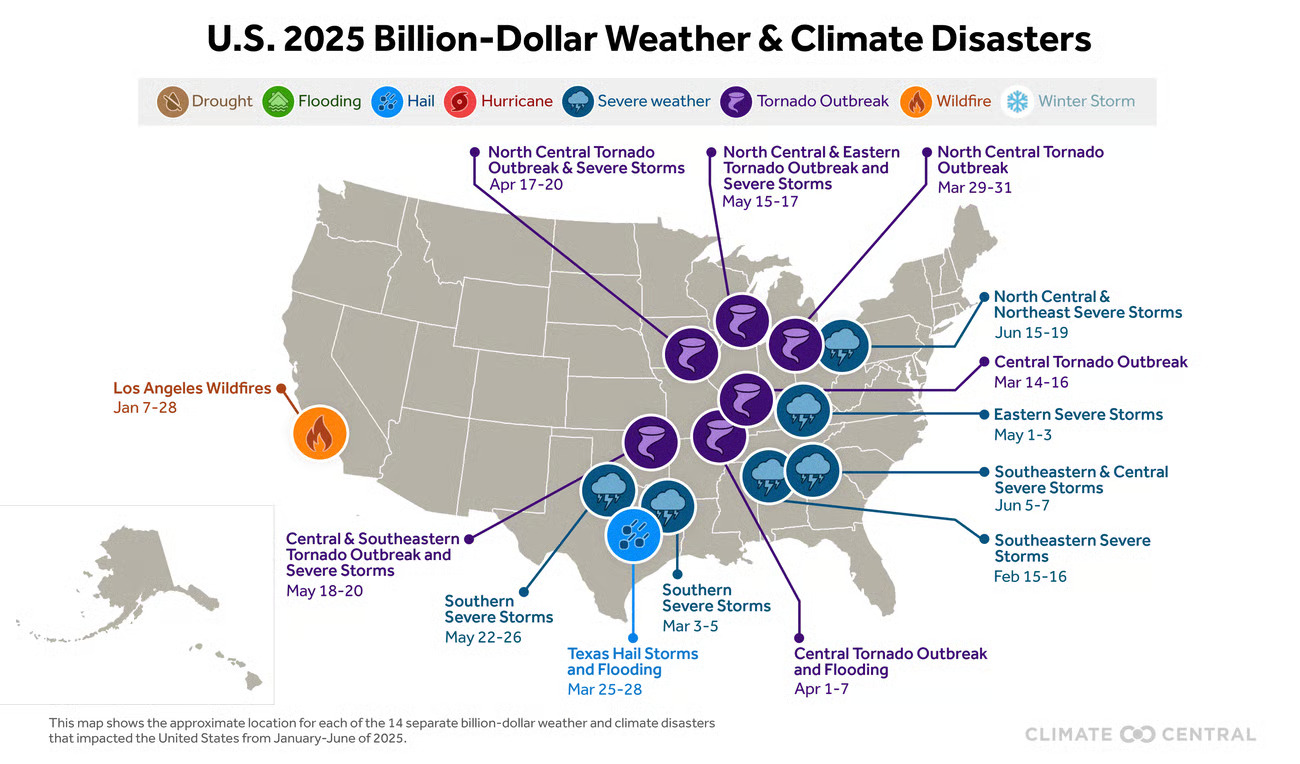

In the first six months of 2025, there were 14 disasters with damages costing just over $101 billion dollars in total. Many of them occurred throughout the Mississippi River Basin — states like Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas and Tennessee were among the hardest hit by severe storms and tornadoes, which caused just over $40 billion dollars in damage.

The January wildfires in Los Angeles resulted in approximately $60 billion in damages — making it the most expensive wildfire on record.

Zachary Labe, a climate scientist at Climate Central, said they brought back the database because they “were hearing from every single sector how important this data is for decision-making and understanding areas that are increasingly at risk for billion-dollar disasters.”

Among those who have typically relied on the database are policy makers, researchers, and local communities. It’s especially important for planning disaster relief and emergency management efforts “because they can focus resources on areas that are seeing big trends in the number of billion-dollars disasters,” Labe said.

Bryan Koon, the president and chief executive officer of the consulting firm Innovative Emergency Management, said the analysis is helpful. His company works with government agencies and other organizations to help with disaster preparedness, response, and recovery.

“These kinds of data sets are very important in the broad scope, at least from my perspective, for trend analysis,” Koon said.

In states like Missouri, for example, he said his company and other interest groups can analyze previous billion dollar disaster data on tornadoes and their frequency over the past decade or two. That information can be used to inform how insurance companies write their policy, how buildings are designed, and how notification systems are structured.

“I want to make sure that we, as a nation, wrap our arms around as much information about these things as we can so that we communicate the threat of future disasters for Americans,” Koon said.

The Mississippi River Cities and Towns Initiative — a cooperative of more than 100 communities between Minnesota and Louisiana — pushed the Trump administration to keep the database open, according to executive director Colin Wellenkamp.

“It was a critical database that showed us where costs associated with disasters were most impactful. What sectors of the economy were hit the hardest by a disaster? Whether it be intense heat, flooding, drought, forest fire, named storm event, or otherwise,” Wellenkamp said.

From a cost-benefit analysis standpoint, said Wellenkamp, the database can tell cities, counties, and states how to spend resources on mitigation to avoid incurring similar costs from future disasters. But industries like manufacturing, construction, and agriculture also want to see the data, he said. That’s because the database’s financial impact analysis includes physical damage to commercial and residential property, losses associated with business interruption and crop destruction, damage to electrical infrastructure, and more.

Other stakeholders that see the value of the database are both the insurance and re-insurance industries.

Franklin Nutter is the president of the Reinsurance Association of America, one of the largest trade groups in the country. The goal of reinsurance is to provide insurance for the insurance companies, stabilizing the industry and playing a role in “the financial management of natural disaster losses,” according to the RAA’s website.

“It’s like an iceberg: the public is made aware of the impact of extreme weather by seeing the graphics (the tip of the iceberg) but most commercial users value the underlying data (the body of the iceberg),” said Nutter by email.

While the billion dollar disaster data is valuable to various financial stakeholders, Nutter said he believes its greatest value comes from providing “public awareness of the increasing extreme weather risk.”

There are many factors that come together to make a billion-dollar disaster — such as weather, infrastructure, population, and location. Labe said that the number of events has been increasing since 1980.

“It’s very likely that 2025 will not be the costliest year on record when we look at the statistics, but it definitely falls into this long-term increasing trend,” he said.

Climate Central is not the only organization trying to pick up the pieces of a resource that was shut down by the federal government or is at risk.

Last month, amid growing concerns over the future of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, the MRCTI announced that it would be partnering with a non-profit called Convoy of Hope to provide aid within 72 hours of disasters for communities along the Mississippi River.

But Wellenkamp said that there aren’t many states that can afford the response and recovery efforts from a billion dollar disaster.

“These [initiatives] are not meant to be permanent solutions,” Wellenkamp said. “These are not meant to replace federal capacity. They are meant to put our cities in a relatively secure position until the federal questions are answered. And the sooner that those answers come, the better.”

For many, the answers will require data.

“Just because the federal government decided they’re not going to do it anymore doesn’t mean it’s not worth doing,” Koon said.

This story is a product of the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk, an independent reporting network based at the University of Missouri in partnership with Report for America, with major funding from the Walton Family Foundation.

weather disasters, climate disasters, NOAA, billion-dollar disasters, natural disaster data, wildfire, tornado, winter storms, climate monitoring, disaster tracking, U.S. weather events, climate resilience

#WeatherDisasters #ClimateChange #NOAA #DisasterTracking #ClimateData #NaturalDisasters #BillionDollarDisasters #WeatherEvents #ClimateResilience #USWeather